I’ve been following Oliver Sacks ever since a friend of mine introduced me to Radiolab three years ago. He became a regular source for many of their episodes and I grew to fall in love with this guy. He became my muse thanks to his personal yet articulate explanation on science.

Sacks had written way too many that I could finished in the short times that I’m aware of him. His writings as a renown neurologists were not merely scientific, but also humane. His journals was said to be not scientific enough because of the amount of personal observation he involved in it, it’s too subjective. “The Man who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” could probably provide you with a glimpse of this. He approached his cases as a human being who understands the science, not as a scientist who just happen to be human being. He never exactly set it apart from the fact that he’s a human being and he’s dealing with human beings, that on its own requires more than just numbers, and facts of symptoms.

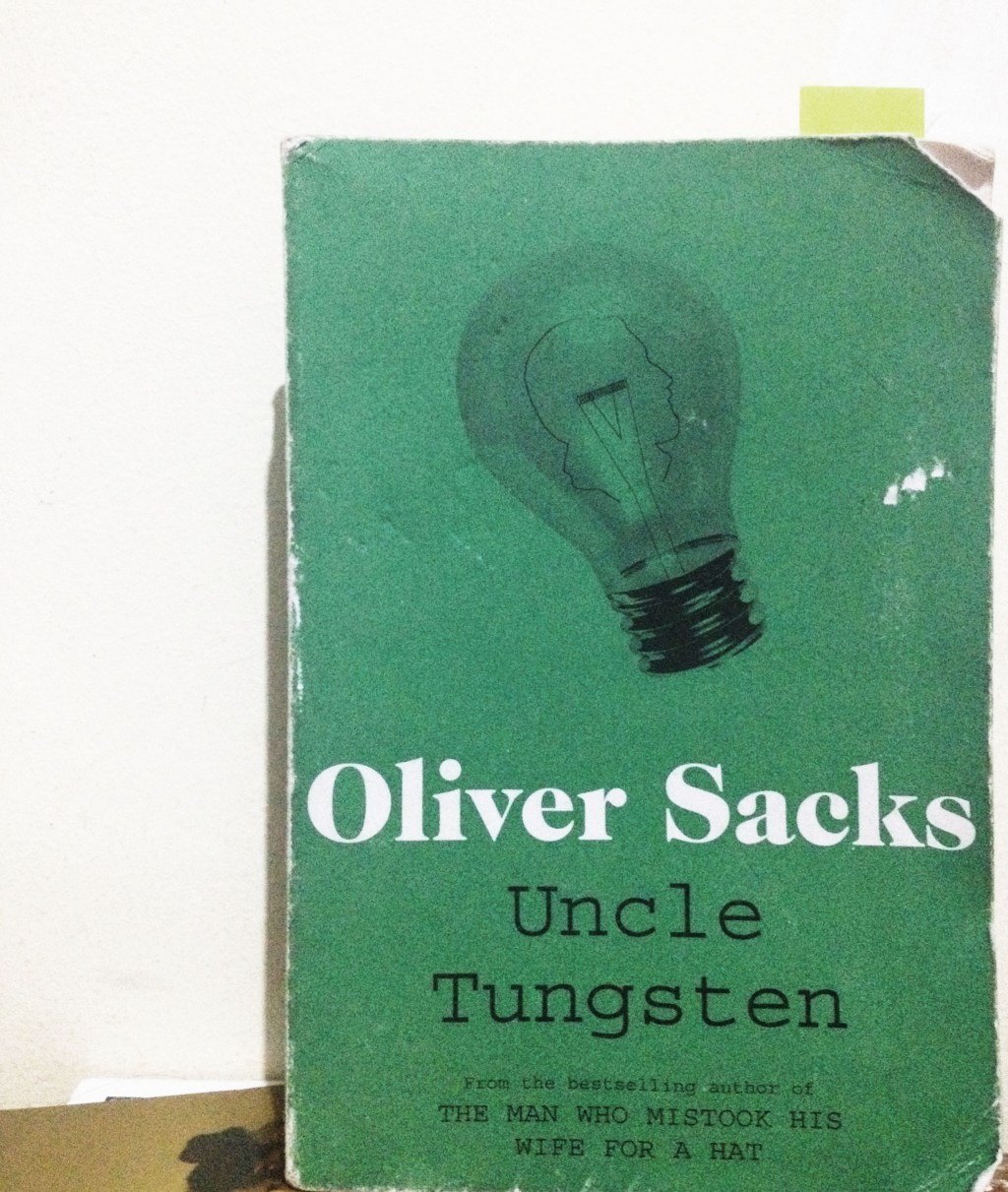

Uncle Tungsten provided me with a background that made him the person he was. It’s an autobiography of his childhood, about how he started to fall in love with science, attributed to Uncle Tungsten who took him into apprenticeship before he was even old enough to do so, how he got obsessed, grew out of love with it, and how the love transformed as an adult. Sacks seemed to breathe chemistry as a young boy. He remembered the table of elements! He must have done an extensive research to be able to comprised his early days – at least sixty years had passed, and create such details emotions.

Science was a big theme in this work, he talked on his obsession on chemistry and the table of elements, how it then expanded to the land of physics, biology, and medicine. In some chapter the science term became very intense. Sacks used a lot of scientific term mundanely. I guess it’s just obsessions that all other kid must have had in their childhood. I had my obsession with numbers, a friend had his on basket ball, his was tungsten. I lost my relationship with science when I entered college. I couldn’t put my head on electromagnetic and I was lost in chemistry. Those were the years that I felt science was just too imaginative, and I couldn’t find my way through it. Now, as I need my imaginations more than ever for the work I’m doing, I couldn’t help to regain my interest in science.

I was devastated when I heard that he passed away. Yet, even with his cancer, he embraced it beautifully as was published in New York Times:

I have been increasingly conscious, for the last 10 years or so, of deaths among my contemporaries. My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself. There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.

Leave a comment